The Great Society

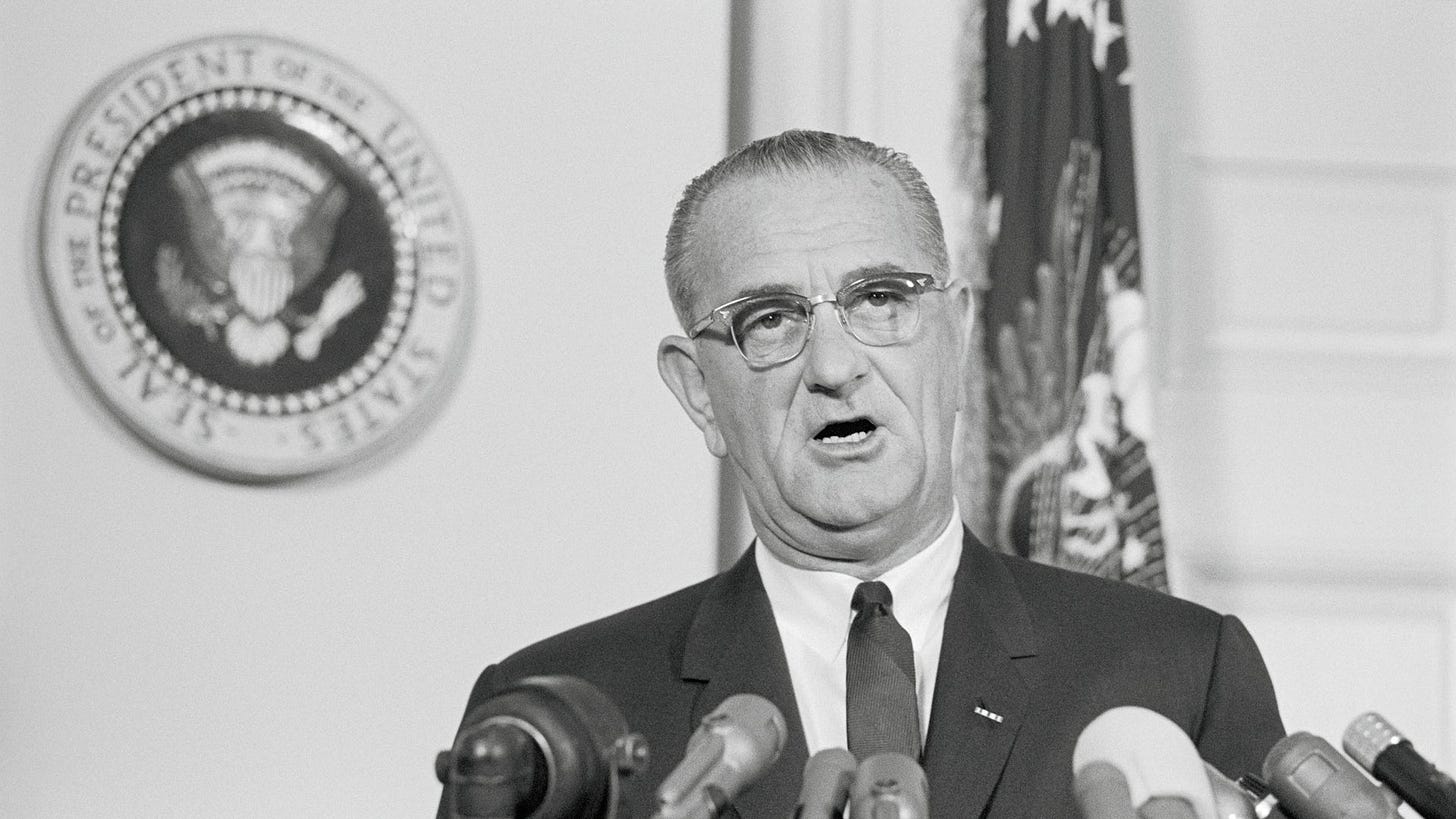

Lyndon Baines Johnson (LBJ), in his first State of the Union address delivered on January 4, 1965, proposed his vision of a "Great Society." A major component of his vision was to initiate an intentional and guided "war on poverty." He called for an expansive program of social welfare legislation, including federal support for education with major emphasis on early childhood education, medical and hospital care for the aged by expanding the existing social security programs, and continued enforcement of the recently enacted Civil Rights Act (1964). He also emphasized the "elimination of the barriers to the right to vote.” The election of November 1964 led to a Democratic landslide and most of those elected shared LBJ's vision, so much of the Great Society legislation was passed.

In the State of the Union address, LBJ described his vision:

"The Great Society rests on abundance and liberty for all. It demands an end to poverty and racial injustice, to which we are totally committed in our time. But that is just the beginning. The Great Society is a place where every child can find knowledge to enrich his mind and enlarge his talents. It is a place where leisure is a welcome chance to build and reflect, not a feared cause of boredom and restlessness. It is a place where the city of man serves not only the needs of the body and the demands of commerce but the desire for beauty and the hunger for community."

In March 1964, LBJ proposed and introduced to Congress the Office for Economic Opportunity and the Economic Opportunity Act (EOA). This legislation established a variety of social programs aimed at facilitating education, health, employment, and general welfare for poor Americans. It became law in August 1964. The act created the Job Corps as a residential education and job-training program for low-income at-risk young people. This program provided structured and directed job training programs with the goal of obtaining meaningful and lasting employment.

The act also established Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA). This program deployed volunteers throughout the country to help fight poverty and to address illiteracy, lack of quality housing, and poor health, among many other objectives, by working on community projects with numerous government and private organizations, communities, and individuals. Through the EOA, the Neighborhood Youth Corps focused on providing training and jobs for young people (ages 16-21) from poor families. These consisted of work-study programs and community action programs. The EOA also provided loans to individuals to start small businesses and to farmers.

The most important program and key to the success of the War on Poverty was the Head Start Program. This is an early education program designed to help prepare children living in poverty for success in public schools. Research demonstrated that some of the difficulties encountered by disadvantaged children were caused by the lack of opportunities created by an impoverished environment for normal cognitive and brain development during the critical early years of life. As we noted in a previous essay, poverty impedes children’s education long before they enter the classroom. Head Start provided, not only cognitive stimulation and learning opportunities for disadvantaged young children, but also provided medical, dental, social service, nutritional, and psychological care for poor preschool children. Head Start included an in-home focus for very young children and another that targeted elementary-school-aged children. The Head Start program is still around (it is not practiced as originally intended) but the other support programs as envisioned by LBJ no longer exist.

Project Follow Through

Project Follow Through, as a component of the War on Poverty, began in 1968 under the sponsorship of the federal government. To this day, it is the most extensive educational research project ever conducted. The charge was to determine the best methods for teaching at-risk children from kindergarten to the 3rd grade. The study included over 200,000 children from 178 diverse geographic communities and ethnic diversities. Twenty-two different models of instruction were compared. The project had strict guidelines and safeguards to assure that the participating schools actually correctly implemented the approach adopted. Comprehensive health services, with a nutritional component as well as medical-dental care, were provided (https://www.nifdl.org).

The evaluation of the effectiveness of Project Follow Through was completed in 1977 mostly during the Nixon/Ford administration, nine years after the program started. The outcome study demonstrated that of the 22 teaching models, one stood out as the most effective teaching strategy - Direct Instruction (DI), a model that uses teacher explanation and modeling combined with student practice and feedback to teach concepts and procedural skills. The following steps are initiated:

Introduction/Review - Set the stage for learning.

Development - Model the expected learning outcomes by providing clear explanations and examples.

Guided Practice - Monitor and engage students with assigned learning tasks.

Closure - Bring the lesson to a conclusion by highlighting what was covered.

Independent Practice - Provide learning tasks that are independent of teacher assistance.

Evaluation - Assess pupil progress.

The results were very powerful, students that participated in DI had significantly higher academic achievement than students in any other programs. They also developed higher self-esteem and self-confidence. No other program approached the positive impact of DI. Further research continued to demonstrate the effectiveness of DI; children who participated in DI continued to outperform their peers and were more likely to finish high school and pursue higher education.

Other findings from Project Follow Through included the importance of parent education as well as applying behavior analysis practices such as providing rewarding consequences for positive behavior. Unfortunately, as happens quite often with politics impacting government decisions, the results of the evaluation were suppressed by the U.S. Office of Education at the time. The Commissioner was of the opinion that even if there was only one successful model, it should be treated like all the other models. After the government spent half a billion dollars on such innovative and important as well as congressionally mandated educational research, they concluded that it was equitable to treat all models the same. Hence there were no selected models.

Go figure.

Obviously, if the government chooses to initiate a research project so that the objective outcome can guide the implementation of practices and policies, they should have to let the results guide them. It is also noted that the Commissioner of Education at the time, Ernest Boyer, assumed it was equitable to treat all models the same and simply promote selected sites. In other words, ignore the scientific data. (Cathay L. Watkins published a detailed monograph in 1997 describing the findings and the government's decision as to what to do with the data - Project Follow Through: A Case Study of Contingencies Influencing Instructional Practices of the Educational Establishment. It can be found here.

Competent and equal education for all is what is going to transform poverty. The fact is that there is a teaching method that has been identified through rigorous research to improve the academic performance of disadvantaged children and make them competitive, and its application has been denied to those children due to mindless government action. No wonder we do not get anywhere in helping the poor become academically competitive so that they can become successful and self-sufficient. The current policies and practices of cash welfare keep the poor, poor and have been doing that for too long.

The War on Poverty - What Went Wrong?

Ron Haskins with the Brookings Institute published a commentary with the above title anticipating the 50th year anniversary of the War on Poverty. He noted, “It is true that poverty declined by 30 percent within five years of Johnson’s declaration of war in 1964, but there has been little progress since the 1960s.” We have returned to the means-tested benefits for the poor that include government assistance and state and federal welfare programs that measure a family’s income against the federal poverty line. Spending more money on the poor without intentionally empowering them to become successful and independent keeps them poor; no change in behavior is required.

Haskins encourages us that “we should also focus attention on three factors that are directly linked to poverty and are under the control of individual Americans - education, family dynamics, and work. In an advanced economy that features technological sophistication and faces international competition, it is difficult to escape poverty without a good education or marketable skill.” It is a frightening fact that the U.S. has been falling behind several other countries in the literacy and numeracy skills of workers. So we also need to address the issue of education in general. Academic achievement test scores in the U.S. demonstrate that the gap between children from poor and middle- and upper-class families has been growing for decades. It's important to acknowledge that there exists a cycle in which socio-economic disadvantages can be transmitted from one generation to the next. This can manifest in circumstances where children from economically disadvantaged backgrounds often face challenges in accessing quality education, which can consequently impact their income prospects as adults. We must focus on behavior change in the poor population with an emphasis on education and family dynamics. We must emphasize skill building with the outcome of being prepared to work, obtain, and maintain a job that is meaningful, rewarding, and can financially free the family from the shackles of poverty.

Noncontingent Reinforcement

Haskins provides us with very convincing statistics. He emphasizes the importance of work reporting, “Nonwork is the surest route to poverty. The poverty rate among full-time workers is 2.9 percent as compared with a poverty rate of 16.6 percent among those working less than full time and about 24 percent for those who don’t work.” Cash welfare most frequently pays bodily able Americans for not working. This ineffective and mostly damaging economic theory of poverty has led to the cash-welfare approach that we are stuck with. Financial assistance, such as cash and material resources do not change human behavior since people are provided with resources non-contingently with respect to any behavior of the recipient. Financial assistance has the potential to be self-defeating because the recipient becomes dependent on the assistance without any further effort on their part to become self-sufficient.

Contingent Reinforcement

Haskins' presentation of compelling statistics highlights the critical relationship between work and poverty, emphasizing that nonwork significantly contributes to higher poverty rates. To address the limitations of the current cash welfare approach, it's imperative to introduce contingencies that align with recipients' potential for self-sufficiency. Pairing cash welfare with requirements such as active job searching, skill development, or community engagement can empower individuals to take ownership of their journey out of poverty. This approach not only fosters a sense of responsibility but also provides a pathway for recipients to enhance their employability and contribute positively to their communities. By incentivizing proactive behaviors, we can break the cycle of dependency and cultivate a culture of self-reliance and long-term economic progress.

What Can We Learn from LBJ’s War on Poverty?

The inception of the War on Poverty in 1965 marked a significant step toward addressing economic disparities. In hindsight, while the explicit approach might not have always been articulated, many of the programs established through legislation aimed to foster positive behavioral changes. Recognizing that poverty reduction requires factors like education, strong family dynamics, and marketable skills, it becomes clear that behavior plays a pivotal role in achieving these goals. Therefore, a comprehensive strategy for poverty alleviation must prioritize both behavior change and thoughtful interventions. Policy implementations that align with defined behaviors, incorporating strategies and practices centered on positive reinforcement, stand as the cornerstone of success. By intentionally guiding and focusing on specific outcomes, and continuously assessing progress, we can adapt our strategies effectively. While this may involve challenges and deliberation, it's essential to emphasize that the alternative is not to negate financial assistance, but rather to augment them with approaches that utilize positive reinforcement to provide crucial resources, such as education and job training, which we know can empower families experiencing poverty. Our forthcoming essay will delve into the potential shape of these policies and practices, highlighting their potential to create a more equitable and prosperous future.

Thank you for reading our Substack and please pass it on!

Francisco I.Perez

Henry S. Pennypacker

Faris Kronfli

For those of you who want to explore behavioral aspects of cultural issues, we suggest Henry S. Pennypacker and Francisco I. Perez Engineering the Upswing: A Blueprint for Reframing our Culture. It can be bought at Amazon or The Cambridge Center for Behavioral Studies (behavior.org). All proceeds benefit the Cambridge Center.

We’re glad you enjoyed it! Thank you, Joan.

Excellent analysis of Johnson's "War on Poverty" , and how it worked and how it didn't. I'm going to mention this post in a post I'm writing today. Thanks!